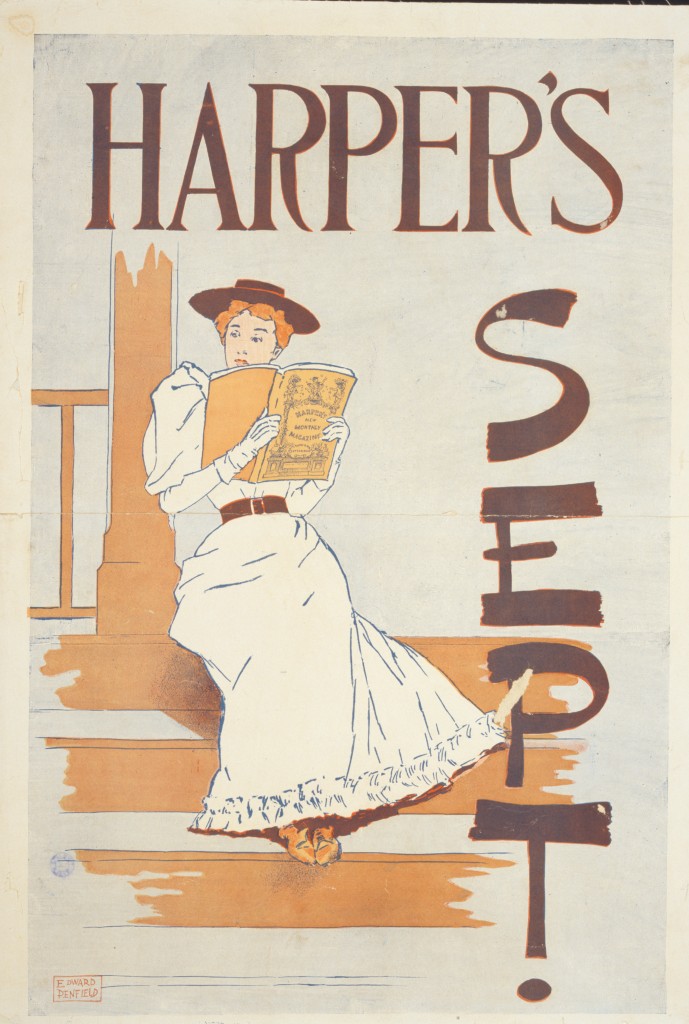

Last week I read reports of an open letter ‘On Justice and Open Debate’ from 151 eminent liberal thinkers to be published in Harper’s magazine in which the authors emphasise the need to ‘uphold the value of robust and even caustic counter-speech from all quarters’ and propose that the ‘way to defeat bad ideas is by exposure, argument, and persuasion, not by trying to silence or wish them away’. This particularly attracted my attention because as a new blogger, the question of what I feel I can and cannot write is of great relevance to me. How much freedom of expression do I really have, what constrains it and do I take it for granted?

What seems like a simple issue turns out to be incredibly nuanced (i.e. prepare for a long blog post!)

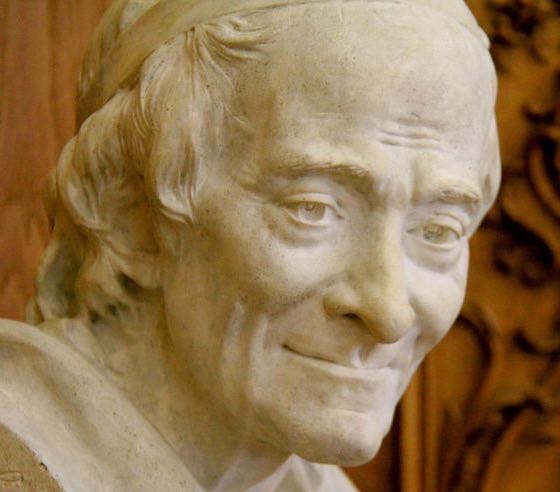

In 1903, a woman named Evelyn Beatrice Hall (S. G. Tallentyre) wrote, ‘I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it’ to encapsulate the beliefs of Voltaire, the 18th century scion of the French Enlightenment movement. The principles of freedom of speech underpin much of the beliefs of modern liberal societies, including the first amendment of the US constitution. Which might also be the premise upon which social media platforms (largely born in America) could base their supposed content neutrality. Mark Zuckerberg might not agree with the content or viewpoint of a particular post on Facebook, but, protected by the principles of the first amendment, he has made billions of dollars out of providing a medium for diverse viewpoints to be shared in the name of free speech.

In all areas of life, freedom and responsibility are deeply intertwined. Freedom with no responsibility however is license, not freedom. An ability to ignore consequences distorts the nature of freedom because it creates an uneven world in which the freedom of a principle actor is snatched at the cost of the loss of freedom of those facing the consequences of that irresponsible actor’s actions. To take a contemporary example, the freedom of bathers to crowd together on beaches is undermining the freedom of others whose livelihoods or even lives may be destroyed by the exercise of this unfettered ‘freedom’. In times of a pandemic, the inevitable result is an authoritarian reaction which results in the restriction of freedom for all.

Long before social media, liberal societies acknowledged that freedom of speech comes with such responsibilities. ‘Democratic’ societies restricted freedom of expression in cases of libel, slander and inciting first violence and then hatred. Freedom of expression without the necessary associated responsibility leads to a parallel authoritarian reaction in the form of censorship, a weapon also often deployed by regimes antagonistic to liberal ideals. The creation of vast electronic platforms does not itself create a new issue, but it does create a megaphone for the existing issues. The human mind attempts to grapple with these questions of freedom by seeing them as external phenomena, problems to be solved and solutions to be found.

But a video of a decapitation of an Islamic State hostage sits somewhere, however distantly, on the same spectrum as Professor Jordan Peterson’s refusal to use gender neutral pronouns. Both present questions of freedom of expression, and both beg the questions, should the authors of media content be constrained, if so, on what basis, and who should decide where that line of constraint lies on this vast spectrum? Is it right, or even sane, that the decision about whether I can view Donald Trump’s penis in a cartoon on Facebook lies with a Catholic mother living in the Philippines?

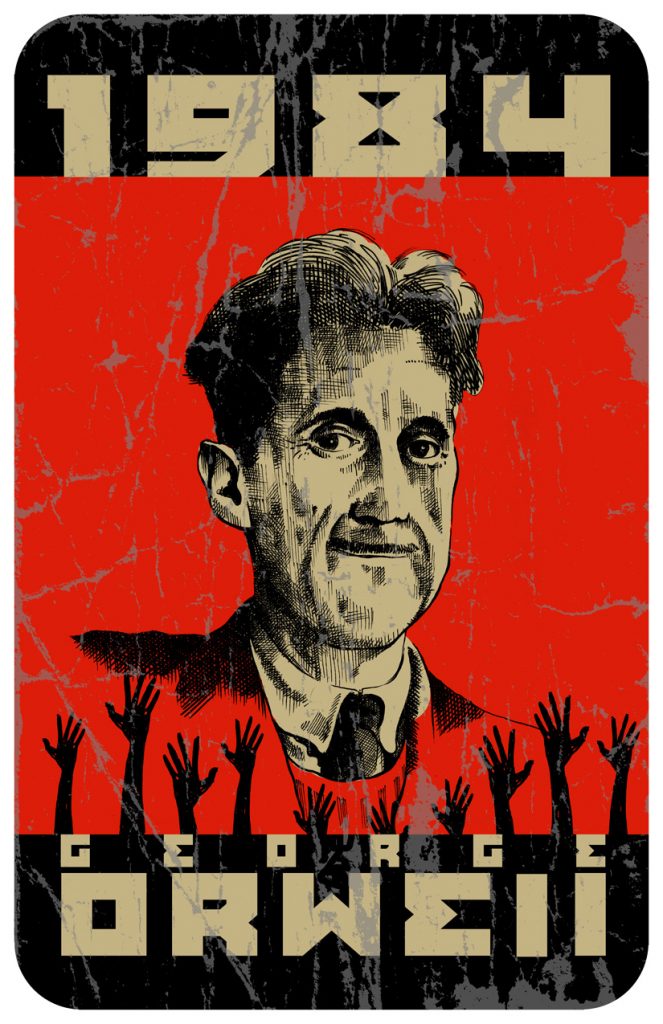

The letter in Harpers magazine addresses the ‘Jordan Peterson’ end of this spectrum which is perceived to be under attack from a growing intolerance using such weapons as peer ostracism and ‘Cancel Culture’. A group unconscious can then arise in which fear of repercussion from militant holders of a different viewpoint can be every bit as effective as direct authoritarian censorship, yet more insidious. This analysis is an extension of George Orwell’s view that ‘what is needed is the right to print what one believes to be true, without having to fear bullying or blackmail from any side.’

Which is a valid destination the mind could reach from a liberal standpoint. But it does not hold up well when travelling down the spectrum to the realms of incitement to violence or ‘hate speech’. The Facebook content cleaners in the Philippines are daily exposed to images of violence and trauma to protect consumers of social media from what we might regard as horrific content, but, as with Don’s penis, somebody somewhere has to make that judgement as to what freedom allows and paradoxically what it forbids.

So have our minds been distracted from another way of considering this? Maybe we should turn the focus of enquiry from the authors of media to the consumers of their output. The rationale for this change becomes clearer as we slide down the spectrum. In the case of Donald Trump’s penis, the relevant question should be, who would wish to view it? Like the Medusa, without a viewer an image has no power. Our desire to view or otherwise consume data is what gives its authors their power.

The power of information lies in its reception rather than its transmission. This significantly changes the gestalt for all media, from the transmitter to the receiver. If I am offended by a viewpoint, that is my responsibility, not the holder or purveyor of the viewpoint. It is only possible to be offensive if I feel offended. My reactions, be they intellectual or emotional, are mine and I should not hold others responsible for them. Further, by doing so, I give the transmitter of that material a power over me which is not theirs to claim. An image with no viewers holds no power.

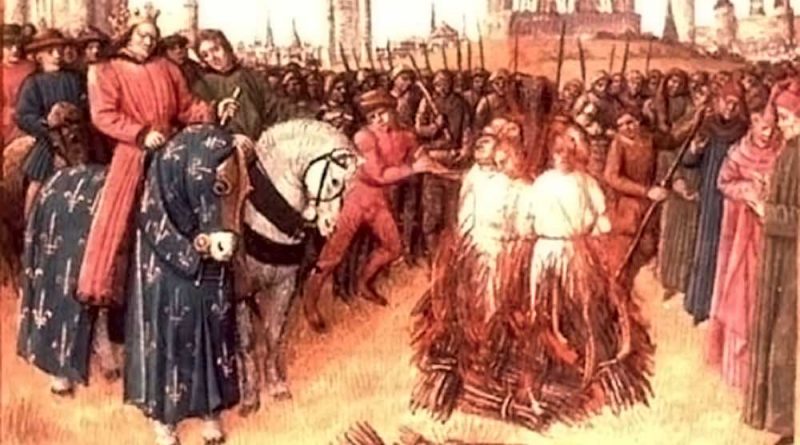

But wait, you might say, what if the person holding those views also possesses physical power over me? Did taking responsibility for their beliefs exempt the Cathars from the Catholic Church’s ‘Holy Inquisition’ in twelfth-century France? Or does it today exempt me from the effects of the politics of Brexit, or my perception of the fallacies of anti-vaxxing protect me from a resulting pandemic? I very much doubt it. And what if my reaction is so strong as to be visceral (def: ‘felt in or as if in the internal organs of the body’).

But a big step on the road would be a shift from a blame culture to a responsibility one. Every time the feeling of ‘who is to blame?’ arises, we could replace it with the question, ‘who is responsible?’ and then further down the road with ‘what is my responsibility?’. This opens up the possibility of escaping from the need for defending the freedom of expression or for resisting censorship as recipients of data take responsibility for what they view and how they respond. The innate paradox, however, is that we urgently need to protect what freedom of expression we still have in order to reach that place where we no longer need to. Meanwhile, I am deeply grateful for the freedoms I enjoy which allow me to write that!

In my view, the USA was already populated by a native people neither morally superior or inferior to the invading Puritans but who had to suffer their encroachments. The Puritans applied the lessons that had been levelled on them both to themselves and the natives.

This curiously parallels the current situation in Israel and future generations might struggle to see the differences between that situation and the exodus from Nazi Europe and the subsequent treatment of the incumbent Palestinians by these same persecuted people. Think Warsaw ghetto and West Bank

Your response touches on so many other issues that I think it will merit a blog in itself! Somewhat from left field, some years ago I read an ‘alternative history’ book called ‘The Years of Rice and Salt’ by Kim Stanley Robinson which started from the hypothesis that the entire population of Europe (not just ~50%) was killed by the Black Death in the mid fourteenth century. The book follows the lives of a number of people (including visits to the bardot) in the non-Christian-dominated world that ensued. An interesting read.

And doesn’t this, at base, point to the eternal dilemma of the spiritual quest…? We are constantly faced with a mind that wants to point the finger and blame others because it can’t take responsibility for pointing at itself. It is so habituated to looking outwards, it’s barely even aware that there is a self worth taking responsibility.

As soon as we take responsibility for being offended, we make ourselves vulnerable. And in the big wide world, who wants to feel vulnerable?

The United States was originally peopled by Pilgrims and Puritans who were fleeing religious intolerance in their home country. In short order a ‘new society, the city on the hill’ was created that was every bit as intolerant as the one they left. Those guys are still around…

The irony is that I can be tolerant of their intolerance, but they are intolerant (of tolerance) …