Did I say that maybe Charles Darwin and other nineteenth century scientists were revolutionary?

Well maybe not so much.

55 BCE was a historic year. At school I learned that it was the year that Britain experienced its first historical invasion. Having conquered Celtic Gaul (and largely instigated the extinction of the Celtic belief systems we saw earlier) Julius Caesar landed a small expeditionary force on the South coast of Britain.

As an interesting aside, this was probably not a random act of military hubris. The Brits love complaining about their weather, but the truth is that the Atlantic Gulf Stream current bathes the British Isles in warmish water and ensures a relatively mild climate throughout the year making it a great environment for agriculture. It is believed that Celtic British agricultural technology was so efficient that its productivity was unmatched until the 20th century (spelt and emmer yields at Butser Celtic farm versus wheat yields in 1900). And this was attractive to the Romans. It’s probably no coincidence that Julius Caesar is known for his military expeditions into Egypt and Britain which later became the Southern and Northern bread baskets of the Romαn Empire.

The other, less well known, event in 55BCE was the death, possibly by suicide, of the Roman poet, Titus Lucretius Carus, at the youngish age of 44 years, though the exact year, like much of Lucretius’s life, is uncertain.

Little may be known of Lucretius, but he left a large unfinished body of work entitled De Rerum Natura, or ‘On the Nature of Things’. He was a disciple of the Greek philosopher, Epicurus, a contemporary of Alexander the Great. Epicurus held that although gods existed, they were far too elevated to be concerned with the trivial affairs of humans, including their creation. Rather, humans were formed of atoms and death was simply the return of the body to its atomic state.

In six books of poetry, Lucretius explores ideas of the natural world from an Epicurean perspective, and in book five he addresses the origins of living beings. On which topic he writes:

‘So many breeds of animals must have died

Back then because those beasts had been denied

The power to provide posterity

With one more generation: what you see

Feeding upon life’s breath must from the start

Have been protected by some cunning art

Or speed or courage. Many still remain

Among us and contribute to our gain

In our protection

…

But those possessing no such qualities,

Who cannot live alone by their own will

Nor be of use to us that we might fill

Their bellies, keeping them unthreatened, lay

At the mercy of so many men for prey

And profit, hampered by the chains they wore

Till they became extinct.’

Here we have a poet-philosopher proposing notions of what came to be known as ‘natural selection’ (‘survival of the fittest’) and even extinction which run contrary to the vast majority of religious Origin myths holding that once created, humans and other organisms have remained unchanged for all time.

Lucretius of course lived almost 2,000 years before Charles Darwin, so clearly this is just some haphazard co-incidence. How could there be any connection between an obscure ancient Roman poet and one of the nineteenth century’s most famous scientists?

It turns out that the text of De Rerum Natura has an interesting history. With the fall of Rome in the fifth century, many classical texts simply disappeared, among them De Rerum Natura. Miraculously, almost a thousand years later a medieval monk named Poggius Florentinus, for whom rediscovering classical texts was something of a hobby, found the text in a monastic library and circulated his new discovery to the literati of Europe.

With its message on materialism, the Epicurean virtue of pleasure and its denial of divine providence, De Rerum Natura was not welcomed by the Catholic Church, especially once the Reformation took hold, but for the same reasons, as the Age of Enlightenment flourished it achieved a wide and eminent readership including the likes of Isaac Newton and Thomas Jefferson

And, Doctor Erasmus Darwin, Charles Darwin’s grandfather, also read De rerum natura in the original Latin. And like Lucretius, Darwin employed the form of the didactic poem to express radical scientific views which echoed those of Lucretius, two millennia earlier:

Organic Life beneath the shoreless waves

Was born and nurs’d in Ocean’s pearly caves;

First forms minute, unseen by spheric glass [ed: i.e. microscope]

Move on the mud, or pierce the watery mass:

These as successive generations bloom.

New powers acquire, and larger limbs assume; [ed: i.e. evolve]

Whence countless groups of vegetation spring,

And breathing realms of fin, and feet, and wing.

The Temple of Nature (1803)

In an essay in his book ‘Zoonomia (or The Laws of Organic Life)’ published between 1794 and 1796, Erasmus writes:

‘[I]t appears that all animals have a similar origin, viz. from a single living filament … All animals therefore, I contend, have a similar cause of their organisation, originating from a single living filament … [sic] with different kinds of animal appetencies; which exist in every gland, and in every moving organ of the body’

which looks like a description of the role of DNA in inheritance and evolution, some one hundred and fifty years before the scientists, Oswald Avery, Colin MacLeod and Maclyn McCarty demonstrated that DNA controls inheritance.

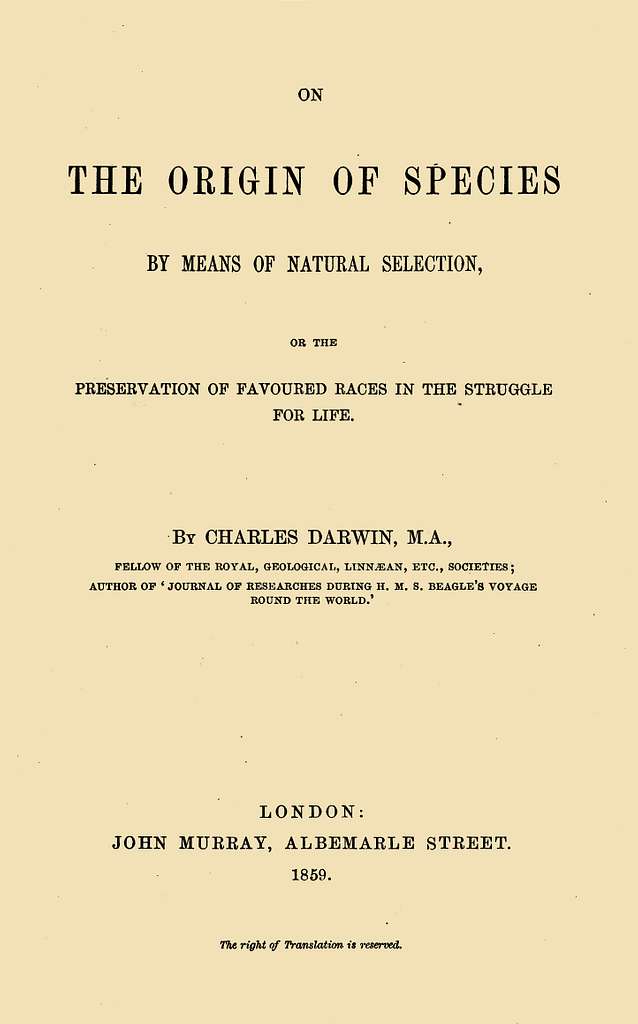

Erasmus then goes on to describe his grandson’s historic contribution to biological science, the doctrine of Natural Selection more than 60 years before publication of Charles’s seminal work, ‘On the Origin of Species’:

‘So the horns of the stag are sharp to offend his adversary, but are branched for the purpose of parrying or receiving the thrusts of horns similar to his own, and have therefore been formed for the purpose of combatting other stags for the exclusive possession of the females. The final cause of this contest among the males seems to be, that the strongest and most active animal should propagate the species, which should thence become improved.’

Although his didactic poetry was immensely popular at the time, by his death in 1802, Erasmus was seen by the government and Establishment as a radical and dangerous French sympathiser with whom Britain was barely half way through a quarter century war. In his final years, he was subjected to venomous conservative satire and ridicule which quite probably influenced his grandson Charles’s extreme caution in publishing his own account of evolution as ‘the origin of species by means of natural selection’ some 60 years later…

Next: Almost six thousand years old …

If you enjoyed reading this Click here to be told of new posts and click on the ‘Feeds and shares…’ section on the right side of the screen.