Nationalism is an infantile disease. It is the measles of mankind

Albert Einstein

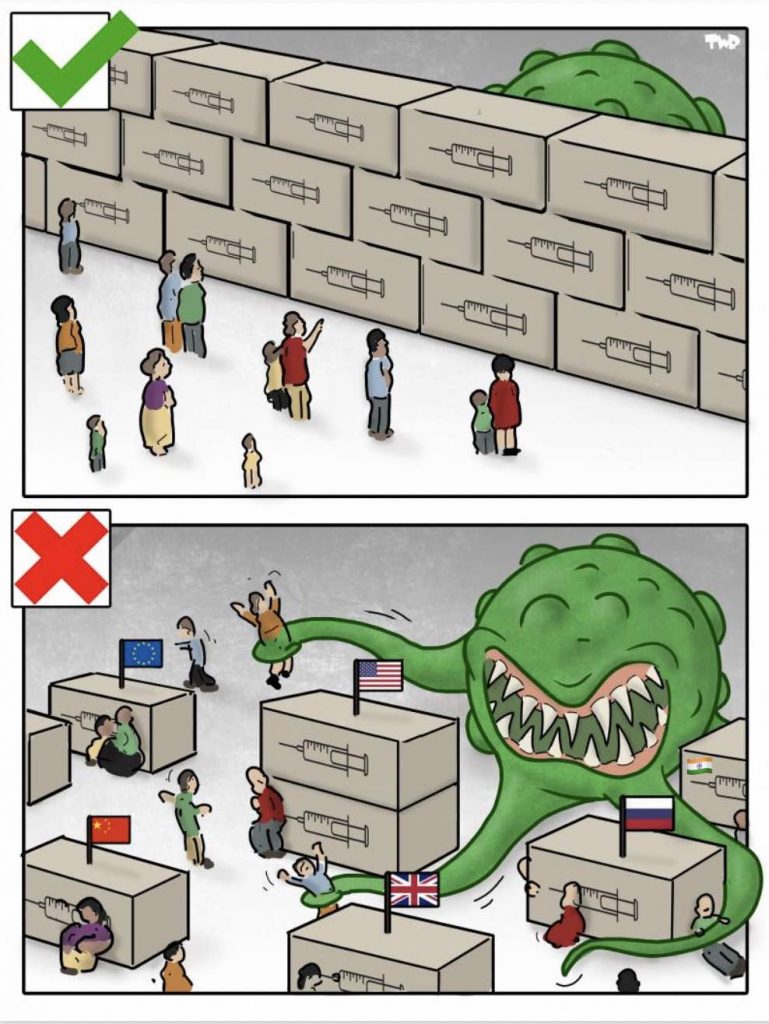

In July 2021, WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus stated that ‘Vaccine nationalism, where a handful of nations have taken the lion’s share, is morally indefensible and an ineffective public health strategy’ adding in December that ‘Populism, narrow nationalism and hoarding of health tools … by a small number of countries undermined equity and created the ideal conditions for the emergence of new variants.’

And now, following the invasion of Ukraine in February, many thousands of people there are dying in the service of this same concept of nationalism. Their societies will honour them as ‘patriots’ as most societies hold loyalty to one’s country a virtue and disloyalty to it a sin, often a crime.

But what exactly is this ‘nation’, to which we are expected to offer unquestioning loyalty, and indeed lay down our lives for, and where did it come from? We think we know because from birth we have lived in and identified with our own particular nations. But in reality, nations are human constructs and the loyalties we feel are artificial and open to manipulation, so may well prove to be inherently destructive to us and even our entire species.

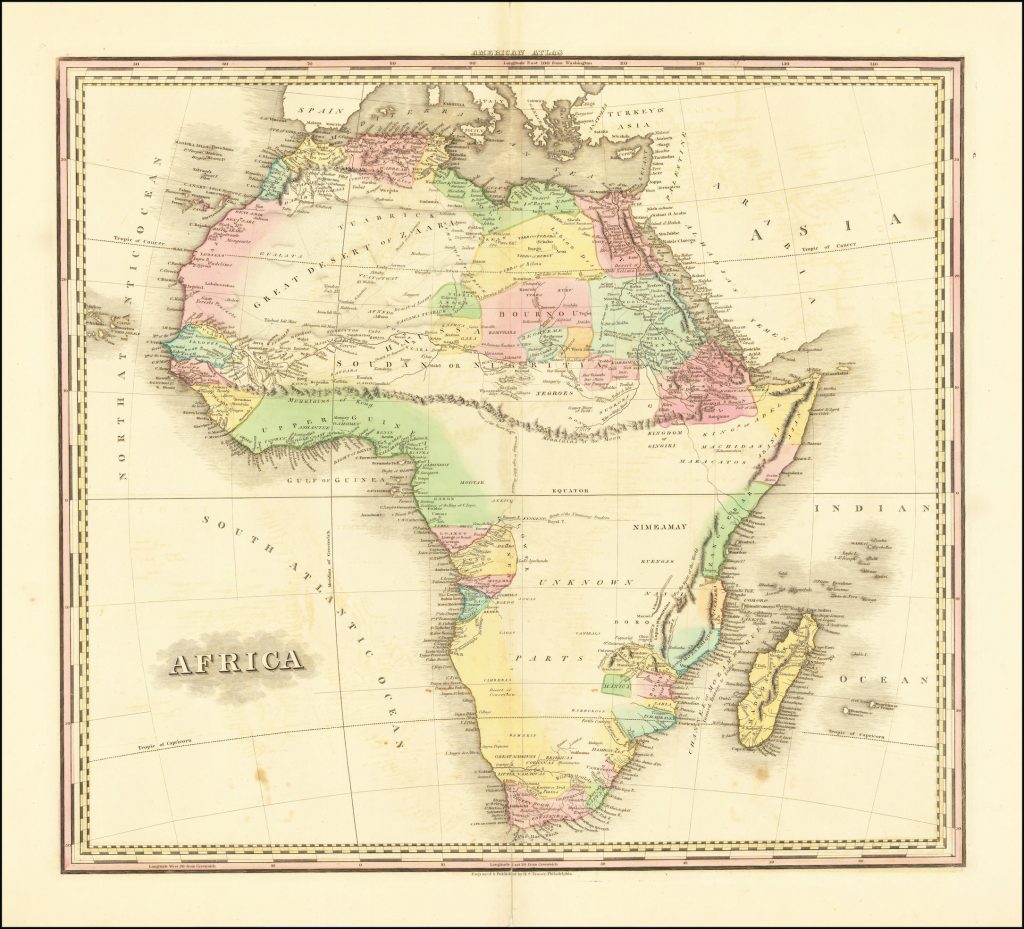

For the most part, nationhood is a modern invention. Ironically, one of the pillars of patriotism and ‘nationhood’ is a shared history. But closer examination suggests that these ‘histories’ are myths and not ‘genuine’ history as we imagine it to be. For example, of the twenty-seven members of the European Union today, only four or maybe six of them (Denmark, France, Portugal, Spain and arguably Netherlands and Sweden) existed in their current form two hundred years ago. And a two hundred year old map of Africa shows perhaps three of the nations we know today.

In 2006, the historian Benedict Anderson observed that nations are, after all, imagined communities. Indeed, he proposed that all communities larger than a village are imagined communities, suggesting that the human need for group identity springs from a very basic drive at the root of all social aggregation be it real or imagined, including nationalism.

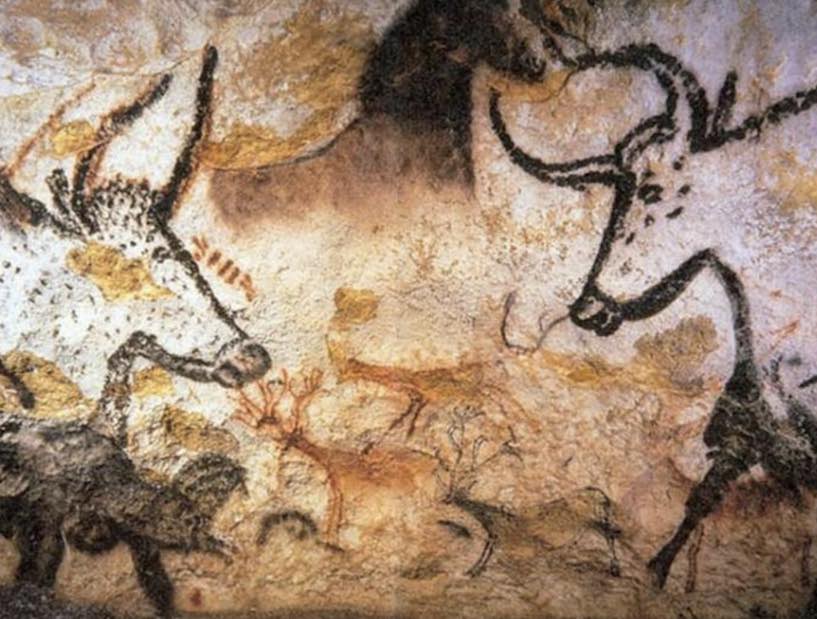

In his best-selling book ‘Sapiens’, Yuval Noah Harari takes this up and argues that one of modern humanity’s most powerful tools, and an essential part of what he calls the ‘Cognitive Revolution’ underlying the dominance of Homo Sapiens as a species, is the ability to create unifying myths: ‘There are no gods in the universe, no nations, no money, no human rights, no laws and no justice outside the common imagination of human beings.’

As a good example, when modern Italy came into being as a ‘nation’ in 1861, the Italian statesman Massimo d’Azeglio is reputed to have said, ‘We have made Italy, now we have to make Italians’. Which says much about the nature of our construct of ‘nations’. In the prize-winning ‘The Pinocchio Effect: On Making Italians’ Professor Suzanne Stewart-Steinberg describes ‘the history of Italy between … 1861 and the rise of fascism in 1922 [as] the history of a state in search of a nation.’

As a good indicator, contrary to how we think of national unity today in a world of national and international electronic media, in 1861 it is estimated that anything from less than 1%, to ‘under 10%’ of the citizens of the new ‘Italy’ actually spoke ‘standard’ Italian.

The Italian example is far from unique. While much of modern Northern Italy was won from the Austrian Empire, many of the nations born in the 18th and 19th century, on both sides of the Atlantic, also arose as a reaction to a fragmentation of empires, like Brazil from Portugal, Mexico and much of South America from Spain, the USA from Great Britain and Greece, Serbia and much of the Balkans from the Ottomans. Only in the nineteenth century did factors essential to the growth of nationalism fall into place. In addition to shared ancestry myths and to hi-jacking histories and cultures from prior ethnic communities, nations require some things that are intrinsically modern, such as a legal code of common rights, a unified economy, unified education systems (propagating the constructed histories), a compact territory and a single political culture.

Because we now live in a world of nation-states, we often believe that has always been the case. We look, for example, at nations like France or Spain and imagine that because an entity of that name has existed for maybe over a thousand years, those nations are that old. But the France of the 21st century is a very different construct from the France of the 16th century, or Tudor England from the ‘Great Britain’ we think of today. These states were the personal fiefdom of their rulers in a way we might find hard to understand. They had subjects, vassals and retainers, not citizens. And although they tended to be geographically continuous, that was not necessarily the case. Considering the lands of the Duke of Burgundy in the 1470s illustrates this: it was not actually possible to journey from one end to the other without leaving his domains.

These are clearly not ‘nations’ as we understand the term today.

Building new nations typically followed a path starting with the development of a ‘subjective’ nationalism, a national sentiment which gives rise to external, objective, political, diplomatic and military action leading to the creation of a physical ‘nation’ with discrete borders and recognised territory. The ‘myth’ of subjective nationalism, that ‘feeling’ of national and patriotic identification can easily be created in us by social manipulation. Social scientists have observed that simply telling people that they belong to the same group is enough to change their behaviour. It follows, therefore, that creating the concept of American, British, Italian (or other) nationality and telling people that they belong to this nation is, in itself, nation-building and makes the Nation a powerful self-generating entity.

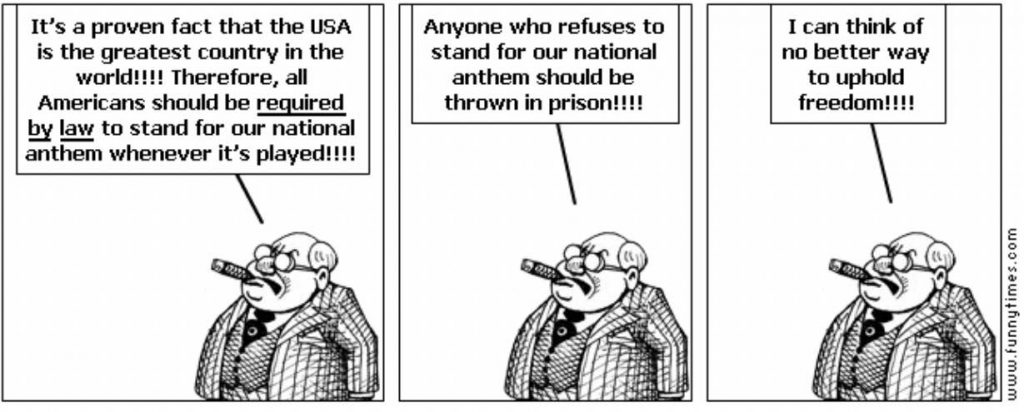

Through the development of legal codes, unified economies and modern political cultures, a sense of nationalism is gradually achieved. This is then cemented by a common language, creating or re-inventing a common culture and history and creating rituals such as anthems, flags, stamps and memorials, and crucially, developing education, so that future generations increasingly define themselves as adherents of that particular Tribe, that pre-eminent Nation.

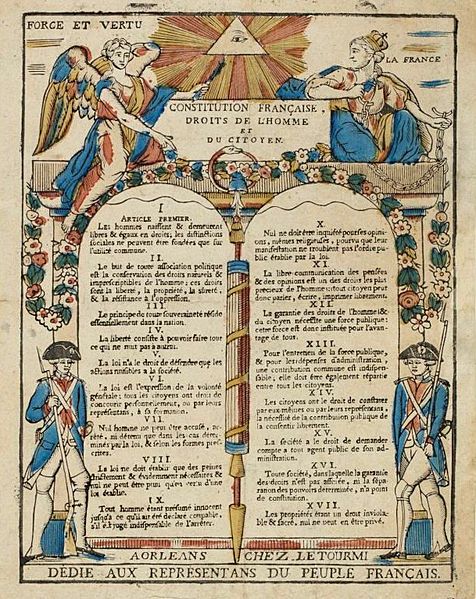

Many would argue that a move from the status of subject or retainer to that of a citizen, albeit of an imagined, mythical community, is a positive step towards individual freedom. At the end of the eighteenth century, the French Revolution, borrowing inspiration from the American Revolution, gave rise to one of the most powerful and enduring expressions of the connection between freedom and nationalism in Clause 3 of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen: ‘The principle of all sovereignty resides essentially in the nation. No body nor individual may exercise any authority which does not proceed directly from the nation.’

However, in reality, too often Nationalism, along with its cousin, Patriotism, proves to be a poison pill we have been conditioned to swallow unquestioningly. George Bernard Shaw described Patriotism as, ‘your conviction that this country is superior to all other countries because you were born in it’. This sense of superiority is not that far from concepts of God’s chosen people or a Master Race and is very appealing to populations in search of purpose and identity in life.

Its appeal gives rise to the Francos, Mussolinis and Hitlers of the twentieth century and more recently an increasingly long list of nationalist leaders in this century: Erdogan, Duterte, Oban, Johnson, Trump, Bolsonaro, Modi, Xi Jinping…. And the inevitable conclusion of such nationalism is that the delicate evolutionary balance between co-operation and competition is disturbed.

At a time when, to avoid planetary climate annihilation, more global co-operation is desperately needed, we have, instead, millions of people having suffered from lack of vaccines and now thousands dying in the Ukraine, all for adherence to the myths and symbols of Nationalism.

Perhaps it’s time that we paid less attention to these echoes from a dying past and pay more attention to the voices of the future:

And maybe we, like viruses, can evolve?

If you enjoyed reading this Click here to be told of new posts and click on the ‘Feeds and shares…’ section on the right side of the screen.

I can see why you gained a First for your recent History degree! Bravo, Gupi x

Here is what Osho says:

https://www.oshotimes.com/insights/the-times/global/a-world-with-no-borders/

I was particularly struck by his warning: “Any day now, the madness of a single politician, and this whole earth will be a heap of dust; it will become a pile of ashes.” This talk was given in 1978!