One of the most dangerous things I was taught in school about Science was that the roots of the word ‘Science’ are the Latin word ‘scio’ meaning ‘I know’ and the noun ‘scientia’ meaning ‘knowledge’. It took many years for me to understand that this, though factually accurate, is not what most Science is actually about. And that this assertion leads many of us to expect things of Science which, by and large, it is not equipped to provide. Foremost amongst these is Certainty.

In recent months, we have all become accustomed to the mantra of choice used by politicians, especially in Western Democracies, ‘We are being guided by the science’, even when in many cases, they so demonstrably are not. This, deliberately or not, is rooted in the same misconception of Science. Even the grammar, with the use of the definite article, ‘the’ Science, implies that something is definite, that Science offers certainty.

This misconception is so pervasive that I was actually in my third year studying for a science degree before I stumbled on a truer interpretation of what science actually is and what it can do. Science is a method, a way of looking at our external universe. It may be the best method that humankind has yet devised for that study, but it is absolutely not the body of knowledge that humans believe they have thus accumulated. In fact, almost the opposite is true. Science progresses through an admission that scientists do not know, that a scientific assertion must be, and has to be, challenged time and time again. Science thrives on doubt.

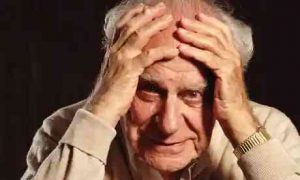

This understanding came to me when I came across the work of Karl Popper. After obtaining a doctorate in psychology, Karl Popper went on to revolutionise the philosophy of science proposing a theory of potential falsifiability as the criterion demarcating science from non-science. In other words, to be scientific, a proposition must have the potential to be proved wrong, to be falsifiable. Which is almost the absolute opposite of certainty. In this world view, Doubting Thomas would be the patron saint of science (apologies to St Albert the Great!).

This then is the basis of the scientific method. Typically, a scientist develops a theory or hypothesis based on observations, tests it through experiments and other means, and then modifies the hypothesis on the basis of the outcome of the tests and experiments. The modified hypothesis is then subjected to a cycle (sometimes over centuries) of retesting and modification as it becomes closer to the observed phenomena it seeks to explain. The key part of this process is that it depends on falsification, not verification. The scientific method does not lead to scientific facts – it simply leads to increasingly robust explanations that fit what we observe around us. As Popper says, ‘the only way to test a hypothesis is to look for all the information that disagrees with it.’ So beware of anyone starting a sentence with, ‘It’s a well known scientific fact’!

This leads politicians to a conundrum. In the face of a life which is, by its very nature, finite, insecure and uncertain, their political survival and power over populations depend on persuading us to feel secure, that they have everything under control, and to do that they need to exude Certainty. To assuage the human fear of impermanence, they project a mirage of certainty by selling the illusion of ‘trust in the science’, in the same way as a bishop in mid fourteenth century Europe might exalt his flock to ‘trust in God’.

Their pandemic, known as the ‘Black Death’ led to the deaths of as many as 60% of the population from a plague with an 80% mortality rate. Many in Medieval Europe were understandably unimpressed by the ‘trust in God’ message of the day and turned instead to mysticism on the one hand and hedonism on the other in response.

If fourteenth century Europeans were sceptical about a god that permitted a disease to kill an estimated 25 million of them, is it reasonable to apply the same scepticism to 21st century politicians whose ‘leadership’ has to date allowed nearly half a million deaths worldwide (at a conservative estimate)?

In the face of humanity’s immense, often self-imposed, survival challenges, now is not the time for people to lose faith in the process of science because politicians hijack its potential for progress to peddle false expectations about what it can and cannot do simply to justify their own political power. ‘The question is not how to get good people to rule; the question is: how to stop the powerful from doing as much damage as they can to us.’ – Karl Popper

Well summarised David. There are few if any truths etched upon the fabric of the universe. Scientific debate is core and key to both develop and challenge existing theories in any field and the idea of consensus is an anathema to further progress.

Sadly with COVID, every academic seems compelled to voice an opinion in order to justify their position and worth, making it very hard to separate the signal from the noise.

Covid-19 has offered many mirrors for us to look at ourselves more clearly. The mix of science, politics and money is one of them, and the toxicity which is becoming clear is disturbing. Though none of this is new, it took a pandemic to make it clear. Let’s hope enough of us can take a look in the mirror and learn from what is reflected back to us.

Thank you Gupi David… yes knowing doesn’t happen for me and not-knowing scares me to death. For me, life is a constant balance act during these uncertain times. I appreciate your insights in your blog. I kinda can relax more knowing that not-knowing is a natural state. And I certainly need to lighten up. Your words soothe me. I prefer you live over a cup of coffee, but your words, your wisdom comfort me. Love is, kp

I heard a podcast some months ago and the person being interviewed (not remembering his name) said that the power of democracy is not that it produces better leaders, but rather has a non-violent process for getting incompetent leaders out of office. He must’ve been paraphrasing Popper.

Yes, to your blog!

Thanks for this. There’s an article in the New Scientist this week about human evolution giving rise to two types of leader manifest, they suggest, in Donald Trump on the one hand and Jacinda Ardern on the other, the “dominance” and “prestige” styles. Amongst our closer primate relatives, the former style is preferred by chimpanzee communities, and the latter by bonobos. It suggests that the kind of leader that populations prefer depends on the degree of threat they feel they face. This model might even predict the outcome of the forthcoming US presidential election.

Hi, congratulations you made it!

I’m impressed – your blog about science gave me something to think about (apart from practising my English). Thank you!