Question: What actually is a virus?

Common counter-narratives: They don’t exist. Nobody has ever seen one. Even if they do exist, they are not alive and so harmless to humans.

I have a friend who has been heard to say both that viruses are not alive, the implication being therefore that they represent no health threat, and that the Sars-Cov-2 virus does not exist because no one has ever seen one.

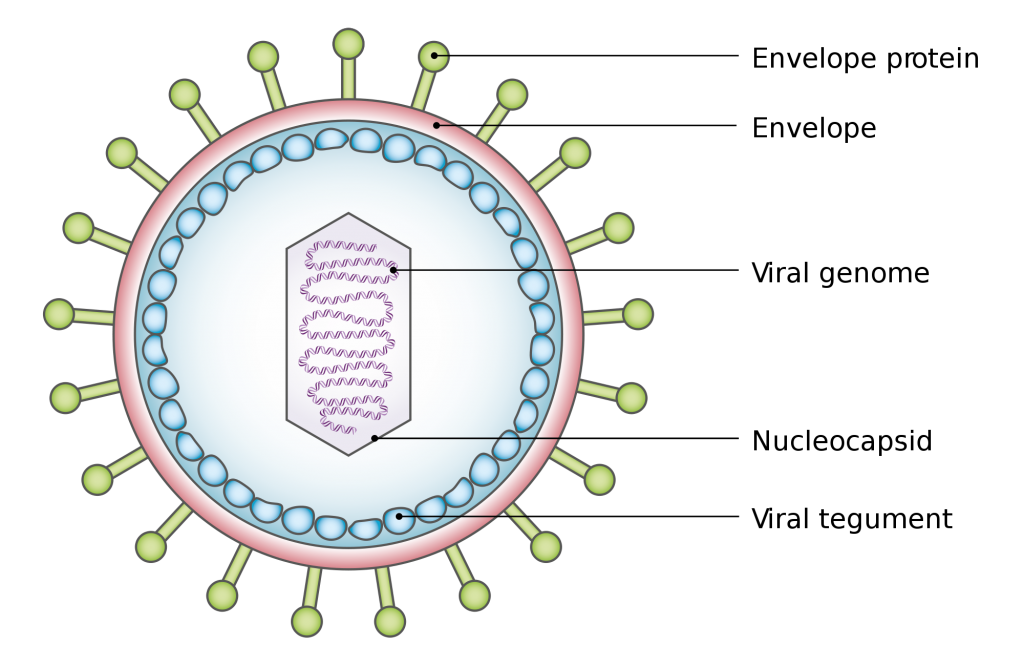

Within the limitations of Science viruses definitely exit. Put simply, they are packages of genetic code carrying the information they need for them to reproduce, within a protective coat.

And there are lots and lots of them. And they are very, very small. An average litre of coastal seawater contains more viruses than there are people on Earth. They come in a range of sizes, but as a rule of thumb, 1000 coronavirus particles (‘virions’) would fit across the width of a human hair.

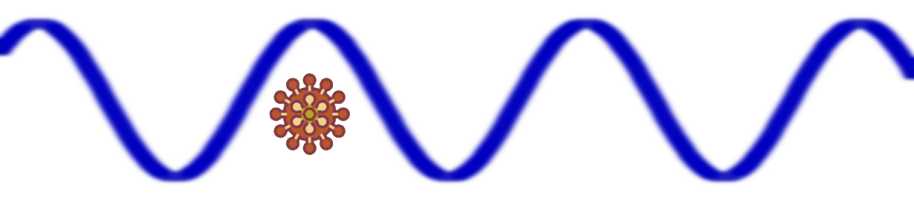

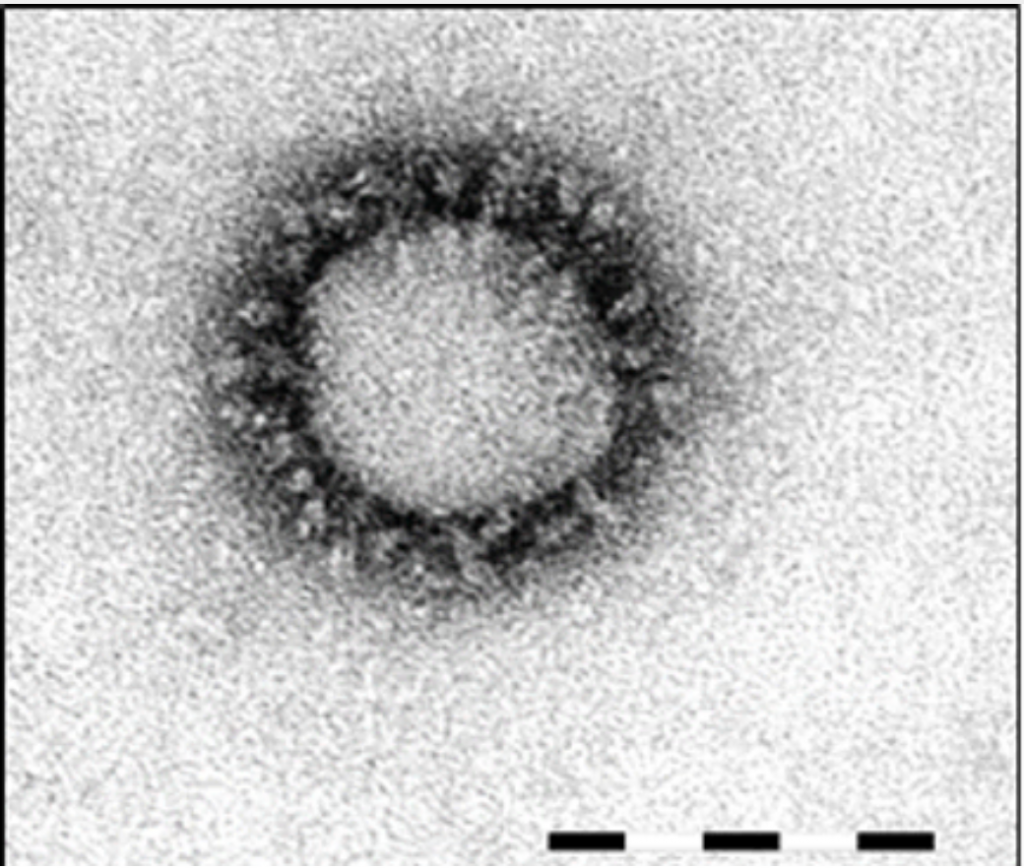

We have microscopes, so why can’t we see a virus? The catch is that for us to ‘see’ a virus (or any object), light has to bounce off that object and into our eyes. Light behaves like a wave, and a virion is so small that it fits within the wavelength of light so we will never be able to see them, no matter how much we magnify the image. But we can use other ways to ‘see’ them which have shorter wave lengths than light, such as electrons. So we can create images of virions in electron microscopes.

So are viruses actually alive? That’s a thorny question because we tend to think of life and death in a binary manner – dead or alive, nothing between. When we ‘die’ a doctor will sign a certificate with the time of death, as though one moment we are ‘alive’ and the next we are ‘dead’. We now know, of course, that this is not true. It actually takes a human body some days to totally stop living.

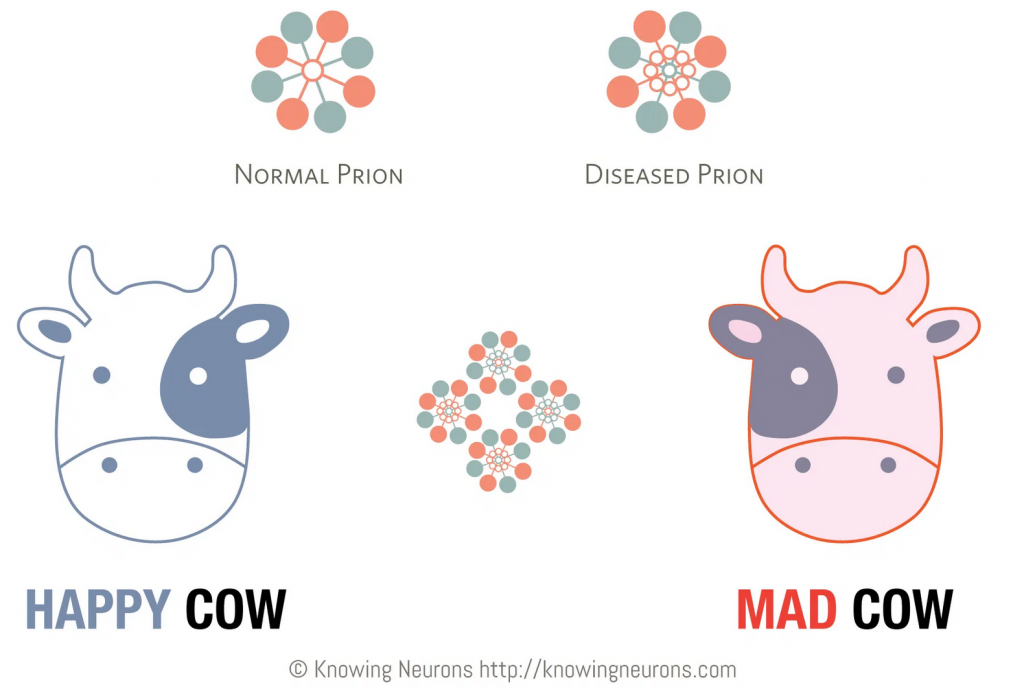

Undead? There are several ‘entities’ occupying a niche between what we intuitively call ‘living’ and ‘non-living’. For example, prions are protein molecules which, when within a host, are capable of transforming existing host proteins to a pathogenic state. They cause diseases like scrapie in sheep and BSE (‘mad cow disease’) in cattle and an associated condition in humans called CJD. Then there are viroids, often associated with plant diseases, which consist of a single strand of genetic material (RNA) which can get inside cells and replicate themselves.

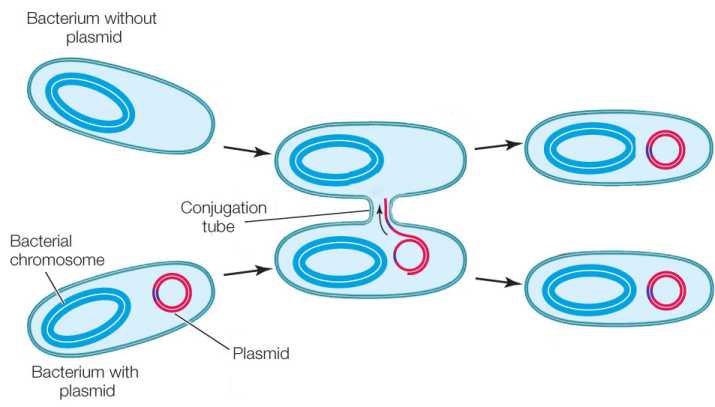

Closer to ‘living’, there are plasmids that are circular strands of DNA which can move between bacteria (usually) and are implicated in the transfer of resistance to antibiotics. All these share an important characteristic with viruses, in that they need to interact with a living host to be ‘active’. Outside of a host, they have no independent ‘life’. To differing degrees, prions, viroids, plasmids and viruses all occupy a land between living and non-living…

So if they’re not alive means they’re no threat to humans, right? Paradoxically, their not being ‘alive’ actually makes them more of a threat to human health as they need to disrupt other living cells (e.g. ours) to perpetuate their existence.

So, although not capable of independent ‘life’, viruses are not dead and this intermediate state makes them more dangerous, not less!