Human beings lie!

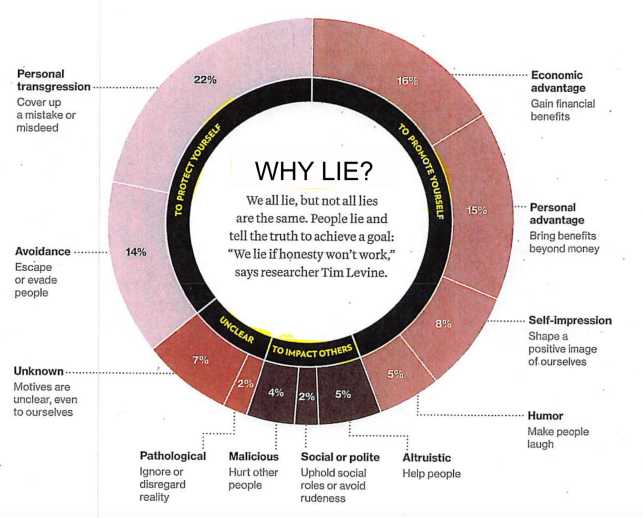

There is good evidence that this is deeply ingrained in our nature, and experiments on children illustrate how we develop the ability to dissemble at a very early age. It can be argued that the ability to fool our fellow human beings offers individuals an evolutionary advantage and that those who are most successful at doing so will prosper and become successful leaders (in other words, politicians). Human lying is therefore akin to the evolution of deceptive strategies in the animal kingdom. Fortunately for humanity, there is an equally good case that for societies to prosper, they need to function together and in co-operation, and that requires a high degree of trust. Paradoxically, being hardwired to be trusting also makes us intrinsically gullible.

All Americans are brought up with the story of George Washington and the cherry tree, ironically itself a lie, in which young George was embraced by his father for being truthful about cutting down his cherry tree.

I have my own, rather painful, version of the ‘rewards for being truthful’ story, with a less happy outcome. In my schooldays, corporal punishment was an accepted practice, and on one occasion, I was among a number of errant 10-year-olds called to the headmaster’s study to receive our just dues. As there were a number of miscreants, we formed a queue in alphabetical order, and my name being near the end of the alphabet, I was last in line.

Experiencing the added distress of watching my fellow victims rush past me in varying degrees of turmoil, it was with some trepidation that I crept through the study door to find the headmaster with his back to me putting away the castigatory instrument. Being an honest fool, I immediately piped up, ‘I think you have forgotten me, sir’. Needless to say, I was not embraced in the manner of George Washington, but duly punished for my earlier sin and equally for my foolishness. Such are life’s lessons.

As I explore elsewhere, we all live on a spectrum of trust, and for most people, this spectrum is individual. I have had conversations (or tried to) with people who distrust all ‘conventional’ sources of information, be they mainstream media, government statistics or scientific papers. I am often amazed however at how readily these people often seem to accept alternative narratives while applying far less critical faculties to them than they do to mainstream information sources.

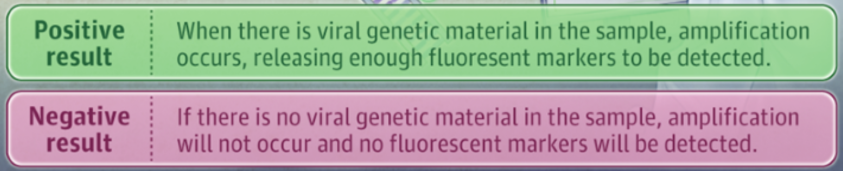

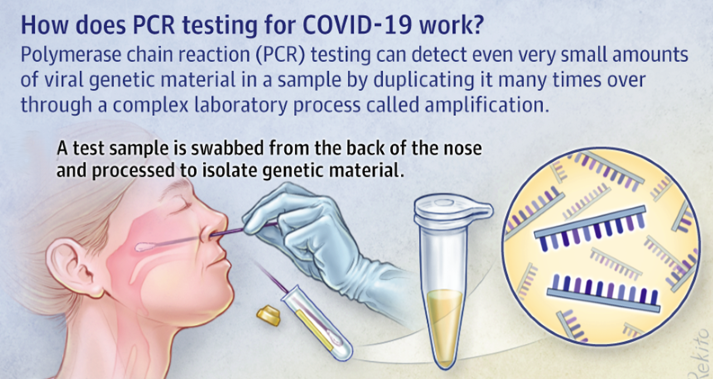

As an illustration of how individual this spectrum of trust is, I recently had an exchange with a German medical doctor who questioned the validity of the research that led up to the development of the PCR tests used throughout the world as the gold standard for confirming Covid-19 cases following research published in January 2020. The result of this was that his spectrum of trust shifted so that he has less faith in scientific publications than I do. To me, his specific questions about the published data were valid and merited investigation, but the generalisation widening this rejection to cover other scientific research papers was not.

Another friend has suggested to me that he would trust how RT (the Russian government sponsored English language TV station) reports on events more than he would the UK’s Guardian newspaper. His spectrum of trust is significantly skewed from mine. But he would be delighted to know that the only mainstream media report I could find about the academic challenges to the PCR paper I mention above was on the RT website…

Checking data is time-consuming. And the world wide web has raised the ‘CLICK’ to divine status. Terms like ‘clickbait’ and ‘doombait’ attest to this. Information flow is now controlled by political organisations (like governments) who would like to control their citizens’ behaviour in some way, or corporations who profit financially from how we click. Sadly, that leaves no upside to accuracy, not to mention truth… Where the objective of a ‘click’ is profit or control, accuracy comes a distant third in the competition for our attention.

Almost all my fact checking and referencing (of which there is a lot) is from scientific papers (or articles derived from them), quality, referenced online encyclopaedias (such as Britannica), mainstream print or broadcast media or quality media websites (such as the BBC or the Guardian) and certain government data (forgive the UK bias in this list, though I do use international sources).

I am aware that all these sources are open to abuse, bias and error. However, my subjective judgement is that in the sources I accept, such error and abuse are in the minority, and, crucially, that the principal purpose of such sources, most of the time, is not to intentionally mislead, in contrast to how I view clickbait-orientated social media. Some might consider this naïve; I prefer it to a permanent state of paranoia. You might describe it as a state of trusting scepticism.

In that vein, we can go on to examine the views often attributed to those amongst us who would be considered ‘anti-vaccine’…

I see. So those of us who are taking their second jabs should expect a stronger reaction than Jab 1. And those of us who are having our first jab after Covid should expect a reaction similar to those taking their second jabs…?

Have I got it right?

If so, all the very opposite of what I’d expected.

Yes. You have got it right. These are the increases in side effects between doses of the Pfizer/Biontech vaccine:

Fatigue: 29% after 1st Dose, 50% after 2nd dose.

Muscle pain: 17% after 1st Dose, 42% after 2nd dose.

Chills and fever: 7% after 1st Dose, 26% after 2nd dose.

As I am due for my second shot next week, I’ll let you know first hand, so to speak.

Hi Gupi, I didn’t respond to your April 20th comment, hoping to get news of how you did after your second jab…

Do you know if people with co-morbidities, pre-existing conditions, suffer more after first and second jabs than your list of percentages and figures tells us?

Here’s a question about vaccinations I can’t wrap my head around… A friend had a mild case of Covid in September last year. Now she’s planning to travel and so recently took an AstraZeneka shot in India in preparation. They do say that even if you’ve had Covid, it’s wise to get a shot as long as it’s at least two months after diagnosis.

She took the jab but had a strong reaction and was in bed for 24 hours feeling “as if she was going to die”.

To me this was counter-intuitive. If she had already had Covid and therefore would have antibodies, surely her reaction to a jab should have been super mild, rather than the reverse…

Now I’m not a medic nor particularly scientifically minded so this baffled me. And it baffles me still.

Can you throw some light on why this should have happened?

Hi. From what you have said, I would suggest that your friend’s body is reacting to the vaccine as if it were a second shot because she has already produced antibodies to the virus from the infection. It is known that vaccination after an infection can increase antibody response sixfold. And ‘around one in five who received their second dose of the Pfizer vaccine logged at least one systemic effect‘. The consensus is that when our immune systems mount an an ‘adaptive immunity’ attack on the viral antigen (in this case the products of the vaccine) it can set up an inflammatory response and it’s this which is causing your friend’s symptoms. Because of this, I’m not making any plans for the three days after my second jab!