I felt a strong sense of irony when I read two news stories on the same day a couple of weeks back. On the day that reports were coming out of India of hospitals running out of oxygen to treat critically ill Covid-19 patients who were apparently left to die, the United States space agency, NASA, announced that a toaster sized device, ‘MOXIE’, they had sent to Mars had successfully manufactured oxygen on the Red Planet, a concept that brought to my mind the final scene in the movie ‘Total Recall’ where Arnie and heroine Melina are miraculously saved by the instant oxygenation of the Martian atmosphere. Away from Hollywood, however, the irony of the juxtapositioning of these two stories says much about the human condition in the 21st century.

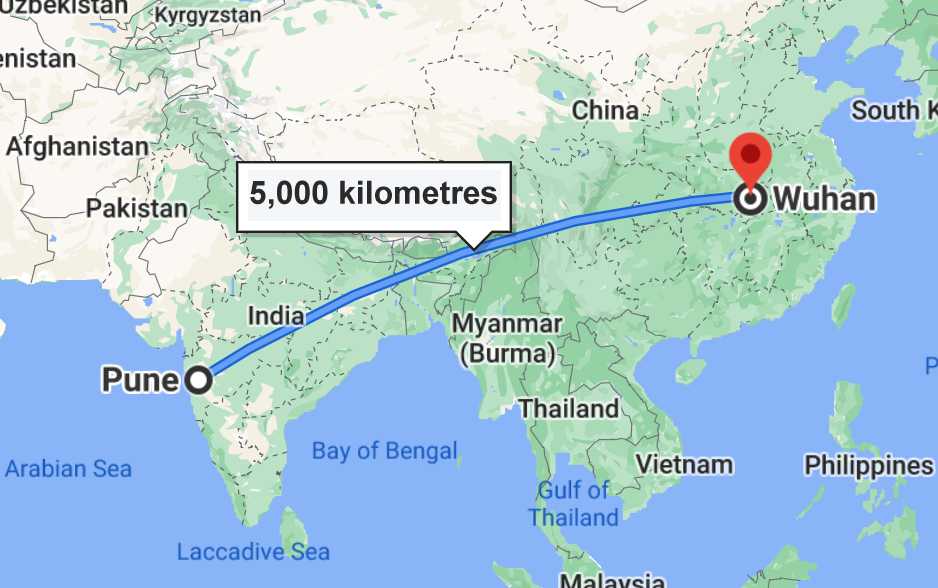

In the early months of 2020 I was visiting the city of Pune in Maharastra, India and reading news reports of an unusual respiratory infection afflicting the people of Wuhan, a city of some 10 million souls, a safe 5,000 kilometres away. My first reaction was that humanity was fortunate that the outbreak was in China because its society and political structures made containment more likely to succeed. However, I was equally concerned that India would be hugely vulnerable to such an infection were it to reach there. On January 30ththe first case was reported in a student returning to the state of Kerala from studying in Wuhan.

I ‘normally’ spend around three months of each year in India, a country I first visited in the late 1980’s and where my partner was born. In the past week or two, we have heard of friends who have numerous family members in hospital including a mother in intensive care who was barely 60 years old and passed away last night. So for me, as for many of my friends, what is happening in India has a personal dimension, and the denials of the data and the science by conspiracy theorists and anti-vaxxers is beyond perplexing in the context of these friends’ personal tragedies in a Covid nightmare.

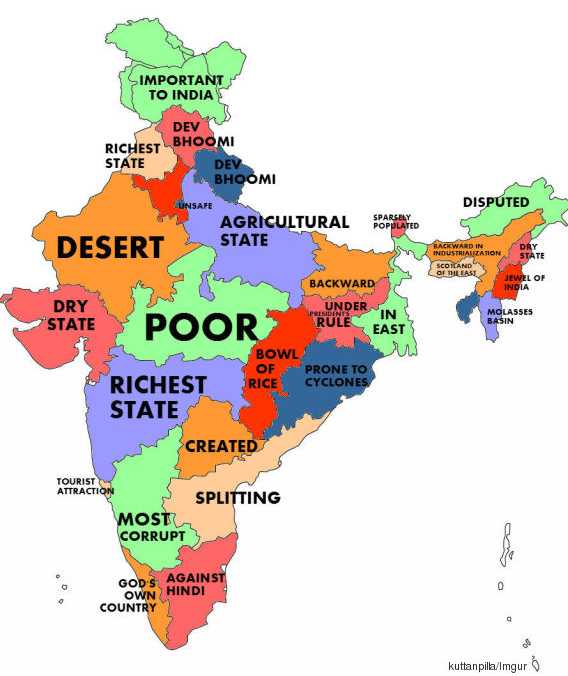

India is a hugely complex country of extraordinary variety and complexity. Indeed one common fallacy about India is to think of it as a single country. It is more properly referred to as a ‘sub-continent’ consisting of 29 states each with their own state government. The ‘Union’ government is based in the Northern city of Delhi, and presides over a federal constitution. Some 31 discrete languages are spoken by Indians and in much of the South of India, the principal official language of Hindi is simply not spoken; among Tamil, Telugu and Malayalam speakers, English is far more likely to be their second language.

As I flew out of India (on schedule) on the 2nd of March last year, my biggest dilemma was whether I should wear a mask during the flight. I decided not to. But I did carry a few masks and some alcohol hand-gel in my luggage. By the time I got to the UK, neither was available in the shops, and on the 11th of March, the WHO declared a pandemic of this newly named disease, Covid-19.

From that single imported case in Kerala at the end of January, by March 25th reported cases were running at 536 per day and rising dramatically. On that day, Narendra Modi announced a three week national lockdown for India: ‘Seeing the present conditions, this lockdown will be for 21 days. This is to save India, save each citizen and save your family. Do not step outside your house. For 21 days, forget what is stepping outside.’

My concerns for India in the event of such a contagion came from some 30 years of experience visiting Pune from which I observed ingrained cultural differences that would make basic pandemic control measures almost inconceivable. In a country of some 1.35 billion people, the concept of ‘personal space’ is much more limited than in Western societies, to say nothing of ‘social distancing’. At that time, almost nobody in India wore face masks except some visiting Westerners who did so for reasons of pollution and hygiene.

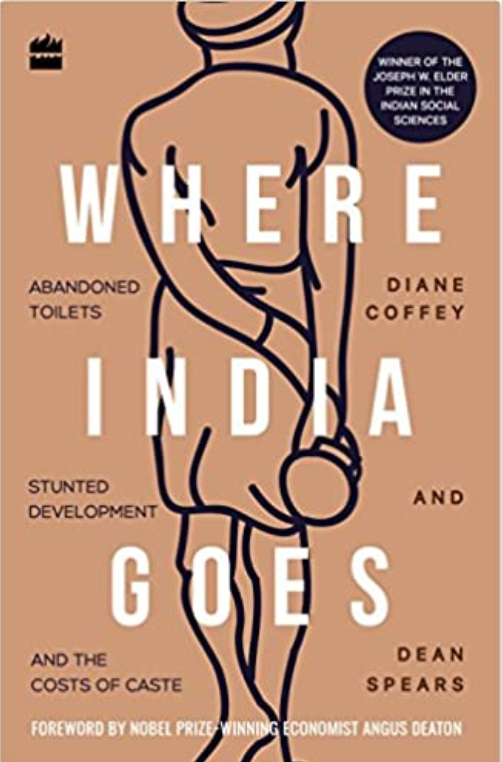

And concepts of public health have a very different meaning in a nation where in 2014 the new prime minister, Narendra Modi, committed in his first Independence Day speech to prioritise building toilets for Indian Households. At that time, just 38% of households in the country had individual toilets and 600 million Indians routinely defecated in the open. To emphasise the dangers of treating India as one nation, however, in one state, Bihar, 73% of rural households defecated in the open, whereas in Kerala only 1% did. To put the issue of public health in context, the 2017 book on the state of sanitation in India, Where India Goes, estimated that certainly over 100,000 and perhaps over 200,000 children under 5 die each year who would otherwise survive if there were no open defecation.

In 2018, annual per capita health expenditure in India was $72.83. This compares with China, where it was $501.06, the UK’s $4,315.43 and the USA’s $10,623.80. India, with a population of 1.35 billion, reportedly has between 75,000 and 90,000 ICU beds, fewer than the number available in England, population 54 million, with over 91,000 ICU bed capacity in NHS hospitals last month.

Somehow, India survived the first wave of Covid-19 without the catastrophic effects I had feared. Many theories have been put forward to explain this unexpected phenomenon including delays in the virus arriving in India, a successful lockdown, younger population demographics and data distortion. The average age of the population in India is 28.4 years (cf Europe at 43 years) which will have reduced mortality and the number of reported cases because asymptomatic infection is much more common amongst the young.

However, the truth is that we may never know what actually happened in India during the first wave, and probably less so in the current wave. The famous adage that ‘truth is the first casualty in war’ should be broadened to ‘truth is the first casualty in war and pandemics’. A toxic mix of nationalist politics and disease can mean that governments have too much at stake to allow information to be freely shared. In 1917 during the First World War, one newspaper went further: ‘the first casualties of war are free speech and free press. And … any other freedom that the people may have’, seemingly even more applicable to life in a pandemic. This is particularly concerning as the honest sharing of data is a bed-rock of good science and global policy making. Neither viruses nor greenhouse gases are respecters of political borders and effective control of either in a globalised world is doomed to failure without the honest sharing of vital data.

Nationalist politicians have a poor track record with Covid-19 throughout the world where the same playbook was played out in 2020 largely because evidence-based policy is not compatible with a nationalist approach to public policy. The BJP government of Narendra Modi in India has a similar style. And one of the hallmarks of nationalist parties is that where the evidence doesn’t support their position, they will either suppress or bend the data. Early in the pandemic in America, the president said of disembarking infected Americans from a cruise ship that had docked in California, [We] ‘don’t need to have the numbers double because of one ship that wasn’t our fault’, as if leaving the sick passengers on the ship somehow meant that they didn’t exist.

In developed countries, one metric for Covid-19 deaths has been a measure of ‘excess mortality’ which is a measurement not of cases where Covid-19 is mentioned on the death certificate, but simply the number of deaths compared with the average number expected for the month in question. In developing countries, very often the systems for recording cases and fatalities are inefficient or largely ineffective. Modelling published by the UK’s Economist on 15th of May suggests that covid-19 has already claimed 7.1 to 12.7 million lives globally against WHO figures of 3.4 million. When approached for excess death figures, the government of China responded, ‘We are sorry to inform you that we do not have the data you requested’, and that of India replied simply ‘These are not available’.

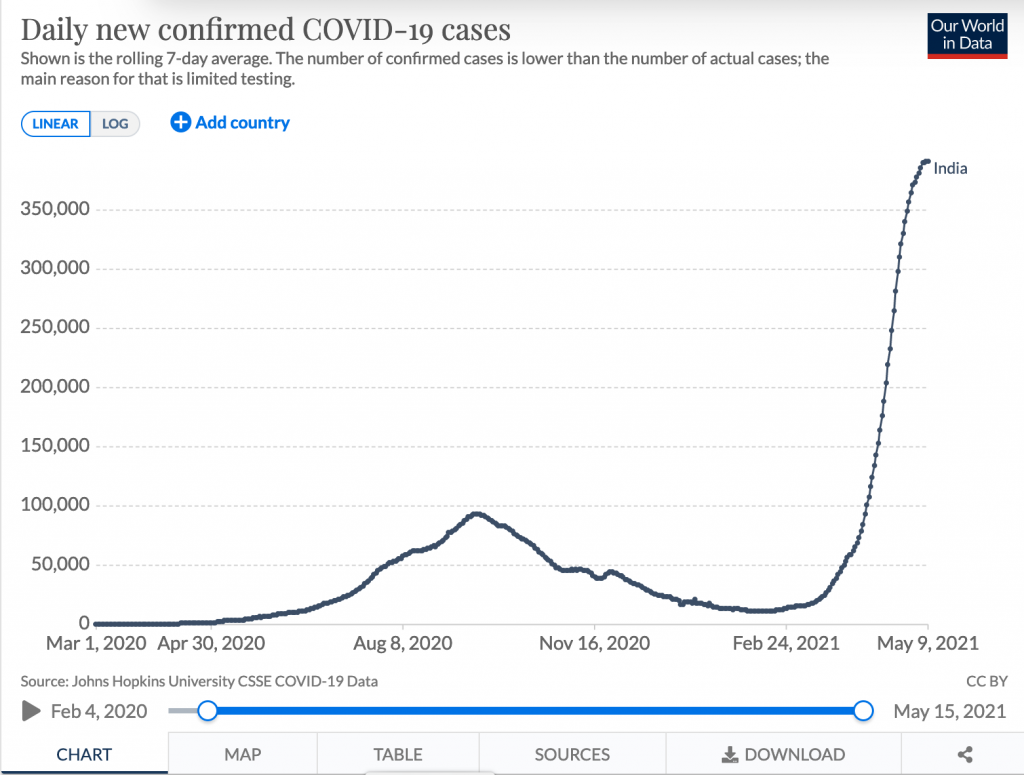

This is a graph of official confirmed cases in India over the past 4 months up until last week. It is clearly a classic exponential growth curve.

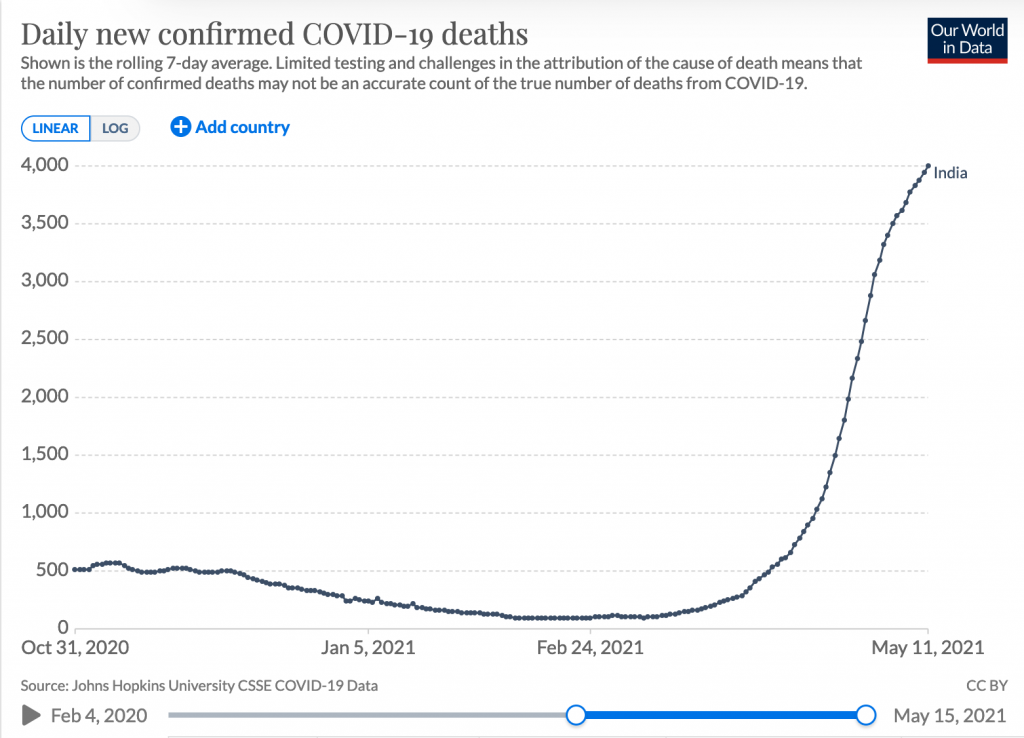

But a more sobering is the graph of confirmed Covid-19 deaths:

Against this background of systemic data blackout, local news media in India have tried to estimate the true death toll. Using a variety of techniques such as checking with hospitals and crematoria, the English language paper, The Hindu, estimated that last month that the state of Gujarat might have undercounted deaths by a factor of 10. The University of Washington’s Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) has estimated that Covid-19 related deaths in India are currently approximately two-thirds of a million, three times higher than the reported figure of about 220,000, a proportion in line with the Economist’s global modelling.

One reason for under-reporting of deaths is that the BJP national government of India ordered that only deaths caused specifically by viral pneumonia would be classified as ‘Covid-19 deaths’.

Where other governments have banned public assembly and restricted religious gatherings, the Indian governing party, the BJP, in an attempt to gain ground in state elections, have engaged in huge political rallies involving tens of thousands of people. And took no action to limit the Kumbh Mela festival, one of the most sacred pilgrimages in Hinduism, in the northern city of Haridwar, in which tens of thousands of devotees immersed themselves in the waters of the Ganges in an archetypical super-spreader event. In fact, it appears that faced with a choice between scientific advice and astrological guidance on the timing of the Kumbh Mela festival, they chose the latter over the former creating the ‘epicentre of a second contagious wave … a tsunami of disease‘.

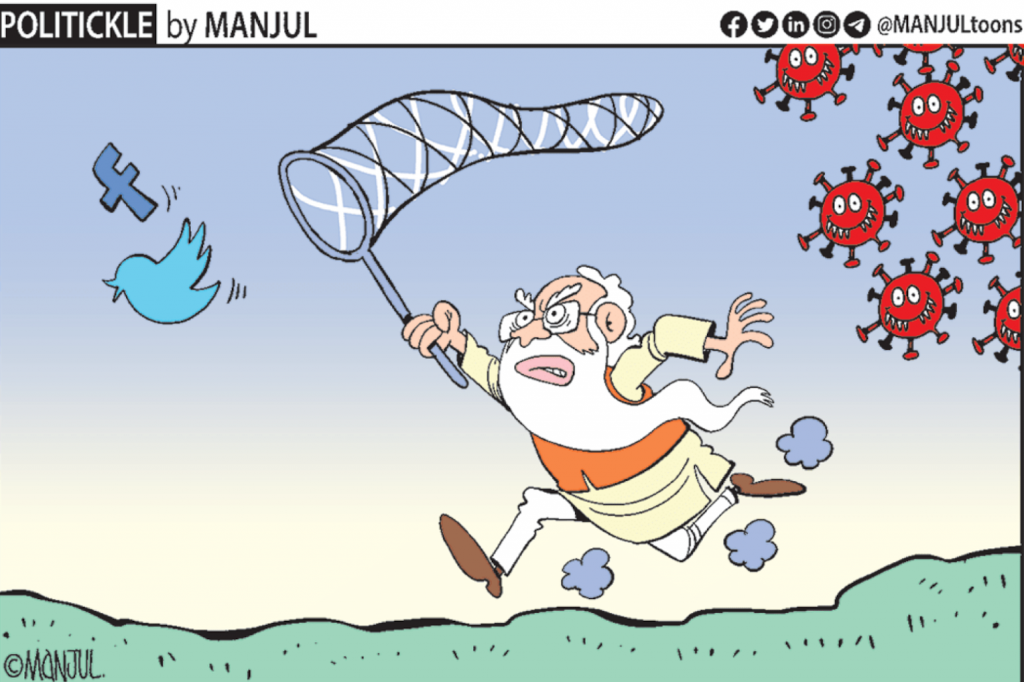

Narendra Modi’s government chose instead to concentrate on demanding that Twitter delete posts criticising its Covid-19 response, on the legal grounds that Indian law allows the country to censor language it considers defamatory or risks inciting violence.

On January 3rd, the Indian government announced emergency approval of the Oxford/Astrazenica vaccine, called in India ‘Covashield’. However, because the BJP agenda could not allow for a ‘foreign’ vaccine to be approved ahead of a home developed Indian vaccine, in a dangerous (but far from unique) mixing of nationalism and science, they also approved ‘Covaxin’, a product developed by an Indian company Bharat Biotech which had barely completed Phase 2 trials and for which no Phase 3 data was available, let alone assessed. In effect, the BJP government was approving the use of the Indian population as its phase 3 trial sample.

And then, in a supreme act of hubris, on January 28th 2021, Modi declared to the assembled world leaders at the World Economic Forum in Davos that India had ‘not only solved our problems but also helped the world fight the pandemic.’ The inevitable nemesis has surely followed that arrogant claim: the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation estimates that India will see a staggering 1.5 million deaths from COVID-19 by the beginning of September at current rates.

In a devastating editorial analysis, the Lancet (one of the UK’s principal medical journals) states that if those predictions come to pass, ‘Modi’s Government would be responsible for presiding over a self-inflicted national catastrophe. India squandered its early successes in controlling COVID-19. Until April, the government’s COVID-19 taskforce had not met in months. The consequences of that decision are clear before us, and India must now restructure its response while the crisis rages…’. And Arundhati Roy of the UK’s Guardian newspaper strongly agrees with a similar analysis as she writes that ‘we are witnessing a crime against humanity’ in the Indian second wave. Sadly the first prerequisites for a restructuring such as proposed by the Lancet are admission of error, culpability and the humility to accept advice and assistance. In a country where foreign aid consisting of ventilators, oxygen supplies and antiviral drugs sat in airport hangers for days awaiting customs clearance and other bureaucratic procedures, this may be too much to hope for.

And for those who protest the imposition of social measures such as mask wearing and social distancing, India represents a tragic and preventable object lesson in what German virologist Christian Drosten calls the ‘Prevention Paradox’ (‘there is no glory in prevention’) and what can then happen when a pandemic gets out of control and medical services are overwhelmed.

And all for largely avoidable reasons. Tragically, India’s current status in the world is as an emblem of what happens when a toxic mix of egos, politics, nationalism and superstition overwhelms the best efforts of science in a tragic abdication of responsibility and failure of leadership.

Meanwhile, in the midst of this unnecessary devastation, anti-vaxxing disseminates its misguided misinformation

If you enjoyed reading this Click here to be told of new posts and click on the ‘Feeds and shares…’ section on the right side of the screen.

Thank you, Gupi, for yet another tragically informative blog.

A WHO report on global excess mortality during the pandemic has now been published after being delayed for some months by opposition from the BJP government of India. Using a variety of sophisticated statistical tools it concludes, ‘We estimate that India has the highest cumulative excess of 4.7 million deaths’. The official mortality figures for India currently stand at 524,190. These numbers are horrifically consistent with the worst predictions at the time this post was written – it’s not surprising that the government of India didn’t want them published!