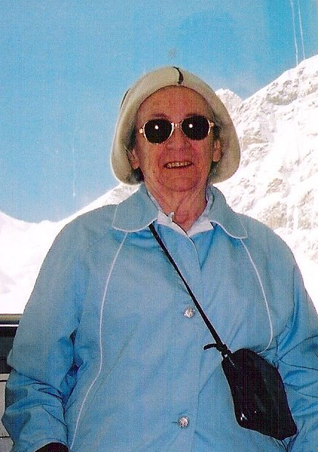

Today is my mother’s one hundredth birthday! And this evening I will drink a toast to celebrate.

This is a piece I wrote a few years ago (slightly edited and with some name changes) for an Open University creative writing project which I offer as an appropriate tribute to my mother some 12 years after she last celebrated her birthday with her family in person.

Dieulafoy Killed My Mother

Isabelle’s passport insisted she was exactly five feet tall. Though she wasn’t quite. It also said she was born on 21-1-28 when she was actually born on 28-1-21, after a bureaucratic mix-up at the embassy during her ‘ex-pat’ time in Egypt. That was before she shrank – old people do; it’s the first signs of our disappearing. So, her passport added a few inches and took away a few years. Either way, at eighty-eight, she could genuinely be described as a ‘little, old, lady’.

It started with the alarm. ‘Personal Alarms’ do work though in the event, Isabelle herself may have preferred to have ‘bled out’ there on the floor. The ambulance arrived before my sister, they took an axe to her sturdy front door, reached her in the bedroom, and with all the urgent ritual of sirens and blue lights, rushed her to the intensive care unit of Oxford’s John Radcliffe. An artery in Isabelle’s stomach had ruptured and she was hemorrhaging.

I was on my way back from the airport to home in Somerset when I got the call from my surviving brother; she was unlikely to live through the night. Although a shock, the call was hardly a surprise. Each passing year, though a gift for me, was increasingly a burden for her. By eight that evening, I had reached Intensive Care.

‘Dieulafoy’s lesion’ is not a phrase well known outside medical circles, an obscure condition accounting for 2% of gastrointestinal bleeding, and which over 90% of sufferers survive. Many feelings crowd into the space left by a death; the bigger the space, the larger the crowd. Guilt, a well known visitor, has a lesser understood extrovert twin, ‘Blame’, and Blame needs to feed on injustice and unfairness. Statistically, it was simply unjust and unfair that Dieulafoy killed my mother. Someone was to blame.

Isabelle was conscious, not actively bleeding, tubes in, tubes out, cables connected to screens, tubes connected to bottles. There was nothing in the ICU for Blame to feed off. The very professional Dr. Joan Metcalf, duty emergency surgeon, explained everything that was being done. Sitting with my mother I faced the inadequacy of my sixty years of life experience, unable even to bridge the gap between my reality and hers, between what I wanted of life and the other reality I was facing. Isabelle expressed what I could not; “I never thought that shuffling off this mortal coil would be so painful.” But I wanted Isabelle to live forever, so I needed her to feel better, get better. I smiled and said something a little teasing, a little joking. Although the image is etched into my mind, I don’t recall the words, only feelings of total helplessness, repressed fear and a rising sense of desperation.

It is said that the heart has ears and eyes of its own; each seemingly trivial little joke conveys love. Isabelle raises a hand, joints disfigured by arthritis these past twenty years, veins suddenly magnified, a tube now attached, and I gently hold it. Each slight movement now carries infinite levels of significance as we escape the level of what we do, and touch, for a few intense moments, who we are.

At her bedside, I am the first to notice the change. Something in Isabelle’s eyes turns inwards, the screens around us emit messages and for a very long, lonely minute I, and I alone, watch Isabelle’s blood pressure hemorrhaging away. Suddenly, her bedside moves from Being back to Doing, and I am gently steered away by swarms of lifesavers.

We spend the night sitting in the little room by the ICU, waiting, conversation limited, reflecting the mood of exhausted intensity. Dr. Joan updates us. If they can’t control the bleeding, she will operate tonight and remove Isabelle’s stomach. Inhabiting strata between Doing and Being, we know she is telling us that Isabelle would not survive such surgery, nor want to.

Miraculously, Isabelle lived through that night and five gastric bleeds over ten days. After a long life as a woman less than five feet tall, Isabelle was a fighter, so she fought on through the two operations to find and seal the lesion. After the second operation, she rolled up her nightdress with an innocent wonder, much as a young child might have done, to show me her row of staples, a gesture I found at once both deeply touching and somehow disturbing, as, completely unselfconsciously, Isabelle displayed her ancient, crumpled, scarred belly.

Surgery completed, as Isabelle moved from the ICU up through Emergency Surgery to the Specialist Gastric Unit, my expectations rose: perhaps Isabelle would live forever, or at least another few years. We started to plan an Autumn trip, even her ninetieth birthday, and I set out on a three-day business trip to Germany.

There, I went online to book a holiday in India for a month later. That was the first ‘phenomenon’. I couldn’t book it. For all kinds of reasons, my chosen flight was not available. Gone midnight, I drifted off to sleep, to be woken by a call on Sunday morning. Isabelle had had a heart attack. It was the oedema. Through all her troubles, the fluid in her body was building up and her heart could no longer take the strain. I caught the next flight back to England. By Sunday night I was at a hotel near Oxford, and as I got into my car on Monday morning, experienced the second ‘phenomenon’: in a moment of transcendental clarity, I knew absolutely that Isabelle was dying. The certainty was so strong, so excruciating, that my mind immediately stuffed it away into the basement of the sub-conscious.

That Monday was a strangely mixed day. On reaching the John Radcliff I was pleased that Isabelle had been moved into a private room, not understanding its real import. Over her bed, at her request, was a ‘DNR’ sign – Do Not Resuscitate. Response times in a private room are necessarily slower. The consultant talked to us about how to reduce the oedema and get Isabelle out of bed, though when I returned to the subject during the nutritionist’s visit, he glanced at me in a manner that briefly awoke my prescience of that morning, along with an understanding that Isabelle was tired with a tiredness that longs for an eternal rest. Her plea to go home was not about a physical place. As I left, she seemed distracted as I held her hand and told her, with surprising difficulty, “I want you to know that I love you”. The heart has ears of its own, so I know I was heard.

“I’ll be back to see you again on Wednesday.”

Driving through my Somerset village on Tuesday afternoon, I took the call. My brother began, in his practical way, “Are you driving? Pull over when you can.” And that’s how I came to learn that Isabelle had died. Five arterial bleeds, two operations, MRSA, severe oedema and finally, two heart attacks.

I kept my promise to Isabelle and went back to see her on Wednesday. Her swollen body laid out in the hospital’s ‘chapel of rest’. Through the tears, pain and finality of severing the umbilical cord, I noticed they hadn’t put her teeth in straight. Foremost among feelings rippling through me in aftershocks was the loss of an unfailing source of unconditional love, and though I was spared from guilt, not so Blame, which fed off the hospital MRSA infection, the slow response time, the consultant’s upbeat assessments, the junior doctor’s evasive replies to my questions.

The day of Isabelle’s funeral, exactly the date I had tried to fly to India, was a surprisingly joyful day. It was a fabulous early Summer’s day and Isabelle managed to arrange several phenomena, from the mysterious cancellation which allowed us to use the grandest lounge for our celebration, to my being locked out of my new car (which Isabelle disliked) with the engine running, a trick that the BMW engineers are still trying to figure out. And I finally escaped the curse of Blame as I told the gathering this Sufi tale:

Once a king dreamed so vividly of Death coming for him by sunset that evening that he awoke in terror and called his wise men to advise him. His minister counselled him to leave the kingdom so that when Death came again, the king would be gone. All day, he rode as fast as he could, and by sunset, left his kingdom. Relaxing under a nearby tree, a shadow fell over him. “You have a fine horse”, said Death. “I am grateful to him. I was worried you may not have reached in time”.

For many months after returning from India (I had no trouble booking now) I visited Isabelle’s grave, each time feeling her presence amidst my grief and loss. One day, shortly after we erected her headstone, she waived farewell with a final ‘phenomenon’. The headstone on the neighbouring plot, her father’s, fell over after half a century. Cemetery staff, the funeral directors, the memorial masons, none of them had come across such a thing before. And, although I periodically return to her grave, from that day I no longer feel the same sense of her presence there.

On Isabelle’s headstone is written simply, ‘Rest and Be Thankful’, taken from the name of an inn on the mountain pass in Scotland near her teenage home. It is, I feel, an appropriate injunction for freedom from the lifelong struggle that her small body faced containing such an immeasurable person.

I think of her fondly every time I cook red cabbage and try to replicate her wizardry with it.

Beautifully and poignantly written.